Title

题目

Pixel-wise recognition for holistic surgical scene understanding

用于整体手术场景理解的像素级识别

01

文献速递介绍

机器人辅助手术相关研究内容翻译 机器人辅助手术(RAS)已成为现代外科医疗实践的重大进展(Goh & Ali, 2022),它为开放式手术提供了微创替代方案,且相比传统腹腔镜技术精度更高(Chuchulo & Ali, 2023)。其先进的器械装备、可视化效果与操作灵活性,不仅为外科医生提供了极大便利,还能显著降低患者并发症发生率(Lanfranco et al., 2004;van Amsterdam et al., 2022)。尽管具备这些优势,机器人辅助手术仍面临若干局限,包括自动化辅助功能有限(Fiorini, 2021)、基于图像的力反馈不足(Rassi & Rassi, 2020),以及特定手术类型的学习曲线陡峭(Kim et al., 2019;Vining et al., 2021)。不过,手术机器人产生的海量数据为开发基于数据的解决方案提供了契机——这类方案可赋予机器人手术认知能力,进而克服当前面临的挑战(Maier-Hein et al., 2017)。 要充分挖掘手术机器人系统的潜力,关键一步是理解机器人内镜捕捉到的视觉数据(Mascagni et al., 2022)。然而,若要全面解读内镜数据,仅靠简单的目标识别远远不够,需采用整体方法,对手术视频的时间维度与空间维度进行全面建模。这种深度理解能为机器人系统带来多方面提升,例如支持增强现实系统(Qian et al., 2020;Tanzi et al., 2021)、实现情境感知辅助(Katić et al., 2013;Kolbinger et al., 2023)、优化手术培训(Maier-Hein et al., 2017),以及推动半自动手术干预技术的发展。 鉴于此,内镜视觉(EV)作为外科数据科学的一个分支,致力于研究图像引导手术认知的核心要素,如手术环境几何结构(Wang et al., 2022a)、手术流程知识(Wagner et al., 2023)以及器械 - 组织交互(Islam et al., 2020;Nwoye et al., 2020)。但内镜视觉领域的各类方法会优先关注不同视觉线索,这导致它们在视觉识别、时间感知与空间粒度方面存在不同需求。例如,手术流程分析(SWA)会研究手术阶段识别等任务,以理解手术流程的时间进展(Padoy et al., 2012)。而要实现这一目标,必然需要一种多识别方法,以识别手术场景中随时间变化的不同作用主体与活动(Twinanda et al., 2016;Nwoye et al., 2022)。因此,手术流程分析已拓展至多任务方向,涵盖手术步骤识别、手势识别、动作识别及器械识别等(Demir et al., 2023)。 尽管手术流程分析的多任务基准数据集已有诸多进展,但在全面理解手术干预的多层次特性方面,现有文献仍存在显著缺口。当前多数手术流程分析基准数据集的一个根本局限在于,它们对内镜图像空间维度的研究较为局限。具体而言,现有基准数据集往往忽略了手术器械的视觉定位——而手术器械是所有内镜手术中的核心作用主体(Nwoye et al., 2022)。相反,手术器械分割或检测任务大多被视为独立于手术流程分析的领域(Jin et al., 2018),且由于收集此类标注耗时费力,极少有内镜基准数据集会将这些任务与手术流程分析相结合。然而,整合手术器械的视觉位置对机器人辅助手术至关重要:当前机器人系统虽能追踪器械的使用情况与运动学数据,却无法将这些信号与器械的视觉位置关联起来(Du et al., 2016;Su et al., 2018;Guan et al., 2023)。此外,器械分割作为视觉识别中粒度最细的任务,可让手术机器人理解器械的形状(Baby et al., 2023)、姿态(Du et al., 2018)及视觉边界(García-Peraza-Herrera et al., 2017)。 当前手术流程分析基准数据集的另一改进方向,涉及对不同视觉感知任务间层级互补性的利用。起初,部分基准数据集将阶段识别(Stauder et al., 2017)、动作识别(Bawa et al., 2021;Goodman et al., 2021)等单一识别任务视为独立任务,而非连贯手术流程中相互关联的组成部分。同样,多任务基准数据集也多聚焦于少数几个视觉理解层级,例如一个视频级任务搭配多个帧级存在性任务(Twinanda et al., 2016;Nwoye et al., 2022),或多个无空间定位的视频级任务(Huaulmé et al., 2021),而非覆盖视觉、时间、空间维度的多个层级。 在我们此前的研究(Valderrama et al., 2022)中,我们为跨多时间与空间粒度研究手术场景奠定了基础:将手术流程建模为“长期视频级任务”(如阶段识别、步骤识别)与“短期时空任务”(如器械定位、原子级视觉动作定位)的层级结构。该建模方法借鉴了Gu等人(2018)提出的“原子视觉动作”概念,以及Barker与Wright(1954)的活动理论——该理论将活动定义为一种层级结构,从作用主体执行的原子级交互这一最精细表达,延伸到复杂目标的宏观推进过程。我们的研究将这些概念应用于手术流程分析,构建了语义任务分层体系:其中手术阶段识别代表最宏观的理解层级,这些阶段可进一步分解为更细粒度的步骤;每个步骤都涉及执行特定的原子级动作,而这些动作又需要使用特定的手术器械。我们提出“手术原子级动作”这一概念,将其作为手术动作识别的空间定位方法,以及手术活动最精细的时间建模方式。该层级结构如图2所示。通过将手术流程拆解为这些既独立又关联的层级,我们既强调了理解各组成部分及其整体动态的重要性,也涵盖了手术宏观与微观要素的核心特征。 在本研究中,我们对原有框架进行了拓展:新增器械实例分割任务以实现最高空间粒度;补充5段全新的全标注视频来扩充数据集,同时整理所有标注信息,并为基准测试定义了特定的数据划分方式与评估指标。此次数据拓展使数据集规模与标注量较初始的PSI-AVA数据集(Valderrama et al., 2022)增加了55%以上。我们将这一改进后的框架命名为“前列腺切除术整体多粒度手术场景理解(GraSP)数据集”。这些改进使我们的基准数据集成为机器人手术领域首个公开可用、包含阶段与步骤标注,且基于真实人体住院手术数据开展器械实例分割任务的数据集。据我们所知,GraSP也是首个以最精细粒度形式涵盖多个长期与短期任务的内镜视觉框架。 除了对基准数据集的拓展,我们还提出了“动作、阶段、步骤与器械分割Transformer(TAPIS)模型”。TAPIS是一种通用的全Transformer架构,专为处理GraSP基准数据集中的各项任务设计。其灵活性体现在两方面:既可作为多任务框架,利用不同粒度的互补任务;也可作为模块化系统,独立处理互不关联的任务。这种设计使TAPIS能无缝适配各类内镜视觉数据集,并应对多种视频识别任务。TAPIS在我们此前“整体手术场景理解”(Valderrama et al., 2022)与“分割”(Ayobi et al., 2023)方法的基础上进行了改进:融入器械分割基准模块,该模块可提供区域建议与形状层面的区域特征,从而提升器械识别与动作识别效果;同时,我们还设计了改进的“区域分类头”,利用Transformer的交叉注意力机制,实现时间嵌入与空间嵌入的充分融合。通过在GraSP数据集及公开基准数据集上与其他基准模型、最先进(SOTA)模型进行对比,我们证实TAPIS在各类任务中均能稳定达到最先进性能。我们在数据集拓展、方法创新与基准验证方面的努力,为外科数据科学领域做出了贡献,也为全面理解手术流程铺平了道路。 综上,本研究的主要贡献如下: 1. 提出用于整体手术场景理解的GraSP数据集——该数据集是PSI-AVA基准数据集的整理与扩充版本,且定义了明确的基准测试数据划分方式; 2. 在基准测试中新增器械实例分割任务; 3. 提出一种通用的基于Transformer的架构,该架构在GraSP框架的所有任务中,性能均显著优于其他基准模型。 为保证公平性与可复现性,并推动整体多粒度手术场景理解领域的进一步研究,我们已将完整的GraSP数据集、源代码及预训练模型按照MIT许可证公开,获取地址为:https://github.com/BCV-Uniandes/GraSP。

Abatract

摘要

This paper presents the Holistic and Multi-Granular Surgical Scene Understanding of Prostatectomies (GraSP)dataset, a curated benchmark that models surgical scene understanding as a hierarchy of complementary taskswith varying levels of granularity. Our approach encompasses long-term tasks, such as surgical phase andstep recognition, and short-term tasks, including surgical instrument segmentation and atomic visual actionsdetection. To exploit our proposed benchmark, we introduce the Transformers for Actions, Phases, Steps, andInstrument Segmentation (TAPIS) model, a general architecture that combines a global video feature extractorwith localized region proposals from an instrument segmentation model to tackle the multi-granularity of ourbenchmark. We demonstrate TAPIS’s versatility and state-of-the-art performance across different tasks throughextensive experimentation on GraSP and alternative benchmarks. This work represents a foundational stepforward in Endoscopic Vision, offering a novel framework for future research towards holistic surgical sceneunderstanding

论文内容翻译 本文介绍了前列腺切除术整体多粒度手术场景理解(GraSP)数据集。该数据集是一个经过精心整理的基准数据集,将手术场景理解建模为具有不同粒度级别的互补任务层次结构。 我们的研究方案涵盖长时任务(如手术阶段识别和步骤识别)与短时任务(包括手术器械分割和原子级视觉动作检测)。为充分利用所提出的基准数据集,我们引入了“动作、阶段、步骤与器械分割Transformer(TAPIS)模型”——这是一种通用架构,它将全局视频特征提取器与来自器械分割模型的局部区域建议相结合,以应对基准数据集中的多粒度任务需求。 通过在GraSP数据集及其他替代基准数据集上开展大量实验,我们证实了TAPIS模型在不同任务中的通用性和最先进性能。本研究是内镜视觉领域的一项基础性进展,为未来整体手术场景理解相关研究提供了新颖的框架。

Background

背景

We performed all optimization and design experimentsin the defined cross-validation folds. For testing, we retrained our bestperforming models on the combined training set (fold one and two) andevaluated the test set to fully utilize the available training data.

我们在预设的交叉验证折(cross-validation folds)中完成了所有优化与设计实验。在测试阶段,为充分利用可用的训练数据,我们将表现最佳的模型在合并训练集(即折1与折2的集合)上重新训练,随后在测试集(test set)上进行性能评估。

Conclusion

结论

We introduced a novel dataset and framework for holistic surgicalscene understanding with a hierarchy of complementary long-term andshort-term tasks with varying levels of temporal and spatial detail. Bycurating and expanding our previous benchmark and including surgicalinstrument instance segmentation, we introduced the first EndoscopicVision dataset with four levels of visual understanding within theirhighest annotation granularity. Through detailed dataset statistics, wehighlighted the challenges presented by GraSP and its representation ofreal-world complexities in robot-assisted surgical procedures. We alsoestablished training, validation, and testing splits to ensure consistentbenchmarking.We developed the TAPIS model to leverage GraSP’s multi-granularannotations. TAPIS surpassed alternative baselines and SOTA modelsin multiple benchmarks, proving its versatility to varying task granularities and formulations. Our instrument segmentation annotationssignificantly improved instrument recognition and provided shape-levelcues that enhanced atomic action detection. Our experiments alsorevealed the complementarity among tasks as TAPIS enhanced per-taskperformance by leveraging multi-task signals.TAPIS’s transformer-based design consistently outperformed alternative baselines, proving the potential of transformer-based approachesand establishing new SOTA results in our benchmark. Moreover, itsconsistent performance across public benchmarks validates the reliability of our methodology and dataset. Hence, this work represents a significant step forward in Endoscopic Vision, promoting a multi-granularunderstanding of surgical procedures and laying the groundwork forholistic surgical scene understanding and image-guided surgical robotintelligence.

我们提出了一个新颖的数据集与框架,用于手术场景的全维度理解。该框架包含具有互补性的长期任务与短期任务层级,这些任务涵盖不同程度的时间与空间细节。通过整理并扩展我们此前的基准数据集,同时纳入手术器械实例分割标注,我们构建了首个内窥镜视觉(Endoscopic Vision)数据集——该数据集在最高标注粒度下,实现了四级视觉理解(标注)。借助详细的数据集统计信息,我们阐明了GraSP数据集所呈现的挑战,及其对机器人辅助手术流程中真实世界复杂性的还原能力。此外,我们还划分了训练集、验证集与测试集,以确保基准测试的一致性。 为充分利用GraSP数据集的多粒度标注信息,我们开发了TAPIS模型。在多个基准测试中,TAPIS的性能均超过了其他基准模型与现有最先进(SOTA)模型,证明其对不同任务粒度与任务形式具有良好的适应性。我们的器械分割标注显著提升了器械识别精度,并提供了“形状级”特征线索,这一线索有效改善了原子级动作检测的性能。实验还表明,任务间存在互补性:TAPIS通过利用多任务信号,实现了各单一任务性能的提升。 TAPIS基于Transformer的设计始终优于其他基准模型,这证实了Transformer架构方法的潜力,并为我们的基准测试建立了新的最先进(SOTA)结果。此外,TAPIS在多个公开基准数据集上均表现出稳定性能,这验证了我们所提方法(方法论)与数据集的可靠性。因此,本研究为内窥镜视觉领域的发展迈出了重要一步,推动了对手术流程的多粒度理解,并为手术场景全维度理解及图像引导手术机器人智能的研究奠定了基础。

Results

结果

Following the experimental setup in Valderrama et al. (2022), wecompare TAPIS with two alternative models: SlowFast (Feichtenhoferet al., 2019) as a CNN-based baseline using ISINet (González et al.,

for region proposals, and an alternative implementation calledTAPIS-VST, which replaces TAPIS’s video feature extractor with theVideo Swin Transformer (VST) (Liu et al., 2022). The results in Table 4 demonstrate that both TAPIS and TAPIS-VST outperform theCNN-based baseline. This finding highlights the advantages of fullytransformer-based approaches, as their enhanced modeling capabilities,powered by long-range attention mechanisms, improve the understanding of complex surgical scenes. Additionally, TAPIS surpasses TAPIS

VST in most tasks while achieving comparable instrument segmentation performance with significantly fewer parameters. We attributeTAPIS-VST’s slight advantage in instrument region classification to itsfiner-grained spatial processing and its larger amount of parameters.Table 4 compares TAPIS with the TAPIR model (Valderrama et al.,2022), which we trained and evaluated using its original implementation details and box proposal network on our current GraSP’s trainand test set. TAPIS significantly outperforms TAPIR across all tasks,achieving a 53% relative improvement in the challenging atomic actiondetection task. This performance difference validates the impact ofour enhanced instrument segmentation annotations and our technicaland methodological advancements. Notably, TAPIR exhibits a slightdecrease in performance for short-term tasks compared to the initiallyreported metrics,6 which we attribute to the curation of our dataset thateliminated biases and included annotations for previously unannotatedand challenging tiny instrument segments.In the following sections, we validate TAPIS by comparing it withpublicly available state-of-the-art (SOTA) models designed for specificsingle tasks similar to those in GraSP. For this purpose, we evaluateTAPIS alongside its alternative baselines and the SOTA models on ourcross-validation set, as well as on alternative benchmarks that featuretasks analogous to those in GraSP. To ensure a fair comparison, wetrain each SOTA model independently for its respective task and adaptall temporal models for offline processing to align with TAPIS’s framework. Similarly, to maintain consistency, all compared methods usingthe same dataset splits and versions. These comparisons also assess theconsistency of our GraSP dataset by analyzing how the performanceranking of various models on external benchmarks aligns with theirperformance on GraSP and the expected performance ranking from thecurrent SOTA.

实验对比与模型验证相关内容翻译 我们参照Valderrama等人(2022)的实验设置,将TAPIS模型与两种对比模型进行性能比较: 1. SlowFast模型(Feichtenhofer等人,2019):作为基于CNN的基准模型,其区域建议(region proposals)由ISINet模型(González等人,2020)生成; 2. TAPIS-VST模型:这是TAPIS的变体实现,将TAPIS中的视频特征提取器替换为视频Swin Transformer(VST)(Liu等人,2022)。 表4的结果显示,TAPIS与TAPIS-VST的性能均优于基于CNN的基准模型。这一结果凸显了全Transformer架构方法的优势——借助长距离注意力机制,这类架构具备更强的建模能力,能更好地理解复杂手术场景。此外,TAPIS在多数任务中性能优于TAPIS-VST,同时在器械分割任务上实现了与TAPIS-VST相当的性能,且模型参数数量显著更少。我们认为,TAPIS-VST在器械区域分类任务中表现出的微弱优势,得益于其更精细的空间处理能力及更多的模型参数。 表4还将TAPIS与TAPIR模型(Valderrama等人,2022)进行了对比。我们按照TAPIR的原始实现细节,结合其边界框建议网络(box proposal network),在当前GraSP数据集的训练集与测试集上对该模型进行了训练和评估。结果显示,TAPIS在所有任务中均显著优于TAPIR,尤其在具有挑战性的原子级动作检测任务中,相对性能提升达53%。这一性能差异验证了以下两点的重要作用:一是我们改进后的器械分割标注,二是我们在技术与方法层面的创新。值得注意的是,与最初报道的指标相比,TAPIR在短期任务中的性能略有下降⁶,我们认为这是由于GraSP数据集经过了数据整理——剔除了原有数据中的偏差,并为此前未标注、且具有挑战性的微小器械片段补充了标注。 在后续章节中,我们将通过以下方式验证TAPIS的性能:将其与当前公开的、针对“与GraSP中任务类似的特定单任务”设计的最先进(SOTA)模型进行对比。为实现这一目标,我们在交叉验证集以及“包含与GraSP中任务类似任务”的其他基准数据集上,对TAPIS、其对比基准模型及各SOTA模型进行了性能评估。为确保对比的公平性,我们针对每个SOTA模型的对应任务独立训练模型,并将所有时间序列模型调整为离线处理模式,以与TAPIS的框架保持一致。同样,为保证一致性,所有对比方法均使用相同的数据集划分方式与数据集版本。这些对比还通过以下分析,对GraSP数据集的一致性进行了验证:分析各类模型在外部基准数据集上的性能排名,与它们在GraSP数据集上的性能排名、以及当前SOTA模型的预期性能排名是否一致。

Figure

图

Fig. 1. The GraSP Dataset formulates a holistic understanding of robot-assisted Radical Prostatectomy videos by studying four hierarchical tasks annotated in their highestgranularity. These tasks include two long-term tasks, recognition of surgical phases and steps, and two short-term tasks, surgical instrument segmentation and atomic actiondetection.

图1 GraSP数据集通过研究四个标注粒度最高的层级任务,实现对机器人辅助根治性前列腺切除术视频的整体理解。这些任务包括两项长期任务(手术阶段识别与手术步骤识别),以及两项短期任务(手术器械分割与原子级动作检测)。

Fig. 2. Hierarchical Structure of GraSP Tasks. This figure illustrates the hierarchicalorganization of tasks in GraSP based on temporal and spatial granularity. Nodesrepresent category labels within each task level, while edges denote connectionsbetween categories across levels. The node names for Phases, Steps, and Instrumentsare category name acronyms as shown in Table 2, while Action nodes are named withthe first three letters of each action label. The intensity of the edge color reflects theco-occurrence of the linked categories based on annotations from GraSP. To enhancevisualization, we reorganized the categories and removed multiple weakly connectededges, as well as highly persistent action categories.

图2 GraSP任务的层级结构 该图基于时间粒度与空间粒度,展示了GraSP数据集中各任务的层级组织关系。节点代表每个任务层级内的类别标签,边代表不同层级类别之间的关联。其中,“阶段(Phases)”“步骤(Steps)”与“器械(Instruments)”的节点名称为类别名称的缩写(详见表2),“动作(Action)”节点名称为各动作标签的前三个字母。 边的颜色深浅基于GraSP数据集的标注信息,反映了所连接类别之间的共现频率;为优化可视化效果,我们对类别进行了重新排布,移除了多条弱连接边及高度重复出现的动作类别。

Fig. 3. Distribution of the percentage of frames per surgical phase category on eachdata split. We organize the graphic in descending order and present correspondencebetween phase IDs and phase labels in Table 2

图3 各数据集划分中每类手术阶段的帧占比分布 本图按帧占比从高到低的顺序排列;阶段ID与阶段标签的对应关系详见表2(Table 2)。

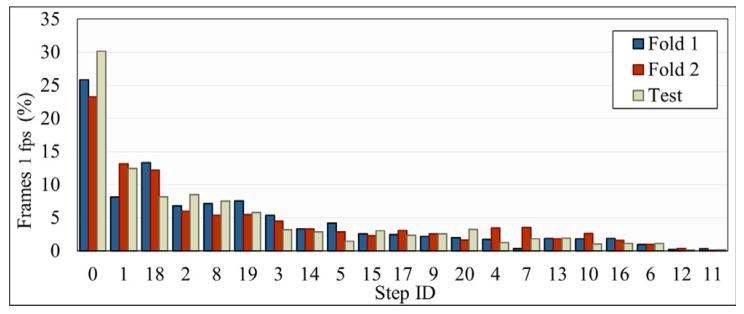

Fig. 4. Distribution of the percentage of frames per surgical step category on eachdata split. We organize the graphic in descending order and present correspondencebetween step IDs and step labels in Table 2.

图4 各数据集划分中每类手术步骤的帧占比分布 本图按帧占比从高到低的顺序排列;步骤ID与步骤标签的对应关系详见表2(Table 2)。

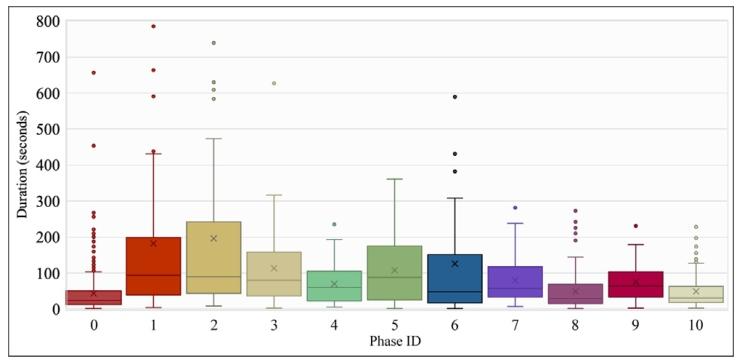

Fig. 5. Boxplot distribution of the duration of each phase category. Each boxplotpresents the distribution in seconds of the period of all the present temporal windowscorresponding to each phase category in our dataset. We clipped this figure to amaximum of 800 s for better visualization; the entire figure is presented in FigureC.10 of the Supplementary Material.

图5 各阶段类别的持续时间箱线图分布 每个箱线图展示了数据集中对应阶段类别所有现存时间窗口的持续时间分布(单位:秒)。 为优化可视化效果,本图将纵轴最大值限定为800秒;完整的箱线图分布可参见补充材料的图C.10(Figure C.10 of the Supplementary Material)。

Fig. 6. Boxplot distribution of the duration of each step category. Each boxplotpresents the distribution in seconds of the period of all the present temporal windowscorresponding to each step category in our dataset. We clipped this figure to amaximum of 800 s for better visualization; the entire figure is presented in FigureC.12 of the Supplementary Material.

图6 各步骤类别的持续时间箱线图分布 每个箱线图展示了数据集中对应步骤类别所有现存时间窗口的持续时间分布(单位:秒)。 为优化可视化效果,本图将纵轴最大值限定为800秒;完整的箱线图分布可参见补充材料的图C.12(Figure C.12 of the Supplementary Material)。

Fig. 7. Distribution of the percentage of instrument instances per instrument typecategory on each data split. We organize the graphic in descending order. Theinstrument categories are Monopolar Curved Scissors (MCS), Bipolar Forceps (BF), LargeNeedle Driver (LND), Suction Instrument (SI), Prograsp Forceps (PF), LaparoscopicInstrument (LI) and Clip Applier (CA).

图7 各数据集划分中每类器械类型的器械实例占比分布 本图按器械实例占比从高到低的顺序排列。涉及的器械类别包括:单极弯剪(MCS)、双极镊子(BF)、大型持针器(LND)、吸引器(SI)、抓钳(PF)、腹腔镜器械(LI)及施夹器(CA)。

Fig. 8. Distribution of the percentage of frames presenting (n) instrument instances perframe on each data split. The percentage of frames at 35-s intervals with (n) instrumentinstances

图8 各数据集划分中“每帧包含n个器械实例”的帧占比分布 该图展示了在各数据集划分下,包含n个器械实例的帧所占的百分比;同时呈现了以35秒为时间间隔的帧中,包含n个器械实例的帧占比情况(注:n代表单帧内器械实例的数量,如n=0表示帧内无器械实例,n=1表示帧内有1个器械实例,以此类推)。

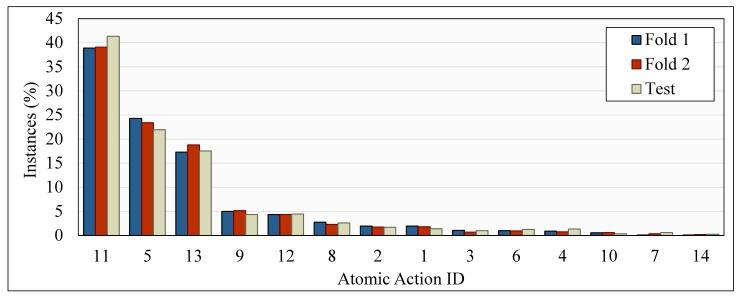

Fig. 9. Distribution of the percentage of instances per atomic action category oneach data split. We consider each annotated action within an instrument instance anindependent atomic action instance. We organize the graphic in descending order andpresent the correspondence between atomic action IDs and atomic action labels in Table2

图9 各数据集划分中每类原子级动作的实例占比分布 本研究将器械实例内每一个带标注的动作均视为独立的原子级动作实例。 本图按原子级动作实例占比从高到低的顺序排列;原子级动作ID与原子级动作标签的对应关系详见表2(Table 2)。

Fig. 10. TAPIS utilizes Mask2Former (Cheng et al., 2022) as its instrument segmentation baseline and MViT (Fan et al., 2021) as its video feature extractor. On the one hand,the segmentation baseline takes an input frame and computes a set of per-segment embeddings by cross-attending learnable object queries with multi-scale features extracted witha visual backbone and processed with a pixel decoder. Then, the model generates a set of binary masks with the dot multiplication between the linearly transformed per-segmentembedding with pixel features from a pixel decoder. On the other hand, the video feature extractor uses a time window centered on the keyframe used for segmentation andcomputes a sequence of spatio-temporal embeddings by patchifying the input video and applying multiple stages made by blocks of Multi Head Pooling Attention. These stagesprogressively reduce the sequence length and increase the number of features. For the long-term tasks, the frame classification head linearly classifies the learnable class token ofthe video feature extractor into either a phase or a step category. For the short-term tasks, a region classification head cross-attends the precalculated segment embeddings fromthe instrument segmentation with the spatio-temporal features, and then they are linearly classified into instruments or action classes

图10 TAPIS模型架构示意图 TAPIS模型以Mask2Former(Cheng等人,2022)作为器械分割基准模型,以MViT(Fan等人,2021)作为视频特征提取器,具体流程分为以下两部分: 一方面,分割基准模型接收输入帧后,先通过视觉骨干网络提取多尺度特征,经像素解码器处理后,再通过可学习目标查询与这些特征进行交叉注意力计算,得到一组“每段(segment)嵌入”;随后,模型将线性变换后的“每段嵌入”与来自像素解码器的像素特征进行点积运算,生成一组二值掩码(binary masks)。 另一方面,视频特征提取器以分割任务所用关键帧为中心选取时间窗口,对输入视频进行分块(patchify)处理后,通过由多头池化注意力(Multi Head Pooling Attention)块构成的多个阶段,计算出时空嵌入序列;这些阶段会逐步缩短序列长度、增加特征数量。 针对长期任务(阶段识别、步骤识别),“帧分类头(frame classification head)”将视频特征提取器中可学习的类别令牌(class token)通过线性分类,映射为阶段或步骤类别。针对短期任务(器械分割、原子级动作检测),“区域分类头(region classification head)”将器械分割得到的预计算“段嵌入”与时空特征进行交叉注意力运算,再通过线性分类映射为器械或动作类别。

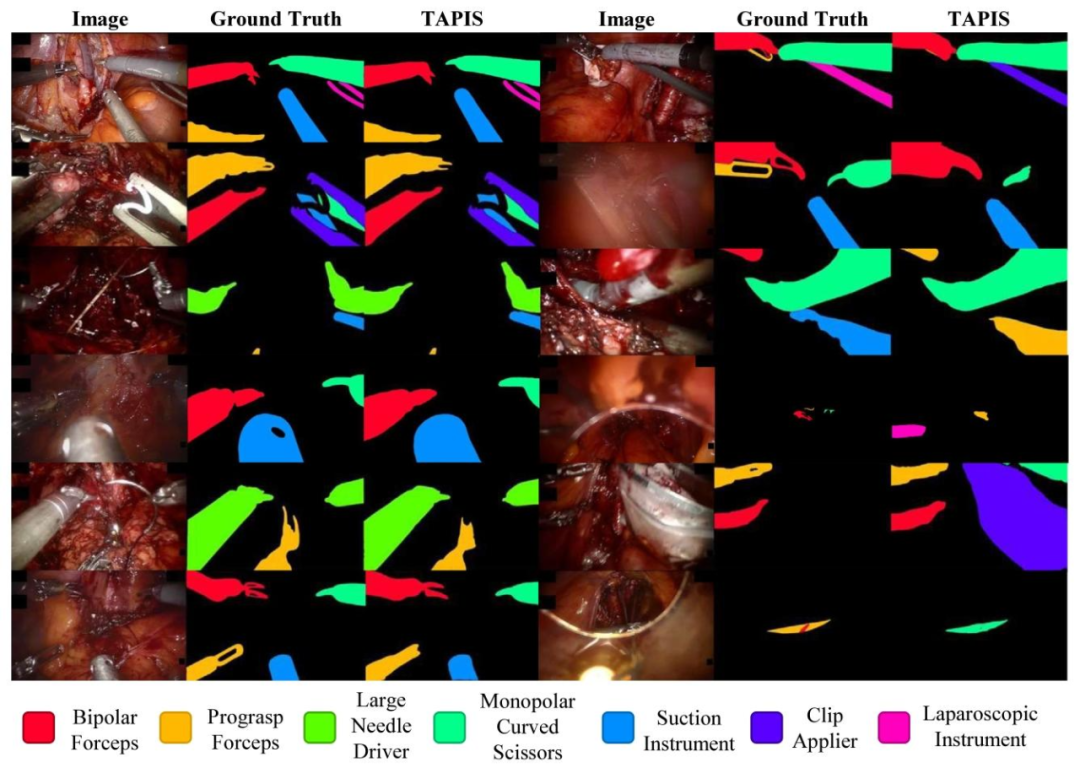

Fig. 11. Qualitative Results of TAPIS in Instrument Segmentation. We present twelve examples of our best model’s segmentation results. The first three rows on the left shownearly perfect results, the next three rows on the left show average results, the first three rows on the right show slight segmentation errors and the last three rows show significantsegmentation errors.

图11 TAPIS模型在器械分割任务中的定性结果 本图展示了TAPIS最优模型分割结果的12个示例,按分割效果分为四类,布局与说明如下: - 左侧前3行:呈现分割效果近乎完美的示例; - 左侧后3行:呈现分割效果中等的示例; - 右侧前3行:呈现存在轻微分割误差的示例; - 右侧后3行:呈现存在明显分割误差的示例。

Table

表

Table 1Our GraSP benchmark compared with current surgical workflow analysis and endoscopic vision datasets. Each row represents a current Endoscopic Vision dataset, and each columnis a possible dataset attribute corresponding to either the inclusion of multiple levels of semantic comprehension, annotations of a particular surgical scene understanding the task,video duration, public availability, or data source type. We show whether an attribute is present (✓), absent (–), has a different formulation (*), or its information is unavailable(?). We also indicate if the source of the provided data is from traditional Laparoscopic Surgery (LS), ex vivo Surgical Training Procedures (ST), Robot-Assisted Surgery on animalsubjects (RASA), or Robot-Assisted Surgery on human subjects (RASH). Our GraSP dataset, shown in bold, is the first publicly available benchmark to provide all the presentedattributes. Note: We combine the Instrument Detection and Instrument Segmentation attributes to identify datasets with instance-level annotations. Datasets with both attributeshave Instrument Instance Segmentation annotations, datasets with only Instrument Detection have bounding box annotations, and datasets with only Instrument Segmentationannotations have Semantic Segmentation annotations.

表1 我们的GraSP基准数据集与现有手术流程分析及内镜视觉数据集的对比 每行代表一个现有内镜视觉(Endoscopic Vision)数据集,每列代表数据集的一项潜在属性,这些属性包括:是否涵盖多语义理解层级、是否包含特定手术场景理解任务的标注、视频时长、是否公开可用,以及数据来源类型。 我们用不同符号表示某一属性的状态:存在(✓)、不存在(–)、表述方式不同(*)、信息未知(?)。同时,我们还标注了数据集的来源类型:传统腹腔镜手术(LS)、体外手术训练流程(ST)、动物受试者机器人辅助手术(RASA),或人类受试者机器人辅助手术(RASH)。 以加粗字体显示的我们的GraSP数据集,是首个具备上述所有属性的公开可用基准数据集。

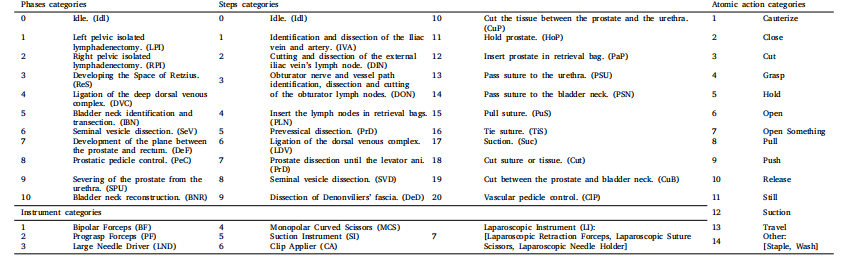

Table 2Category sets for all the presented tasks in GraSP. We present the defined sets of semantic categories for each proposed task in our GraSP dataset. We showcase the ID numberand the defined label name for each phase, step, instrument, or atomic action category.

表2 GraSP数据集中所有涉及任务的类别集合 本表格列出了GraSP数据集中各拟议任务所定义的语义类别集合,展示了每个阶段、步骤、器械或原子级动作类别的ID编号及对应的定义标签名称。

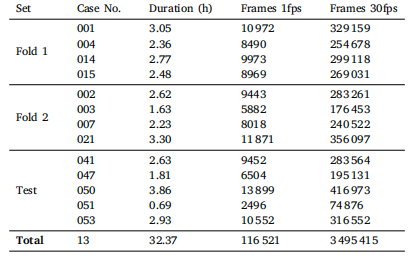

Table 3Distribution of the number of frames on each defined dataset split. The Table presentsthe duration in seconds and the number of frames sampled at 1fps and 30fps of eachcollected Case in our dataset. Each Case corresponds to an entire surgery performed.We also show our predefined dataset partition into Fold 1 and Fold 2 for two-foldcross-validation and a Test set for final model testing

表3 各定义数据集划分中的帧数量分布 该表呈现了数据集中每个病例(Case)的时长(以秒为单位),以及在1帧/秒(1fps)和30帧/秒(30fps)采样率下的帧数量。其中,每个病例对应一台完整的手术。 此外,表中还展示了我们预先定义的数据集划分方式:分为用于两折交叉验证的“折1(Fold 1)”和“折2(Fold 2)”,以及用于模型最终测试的“测试集(Test set)”。

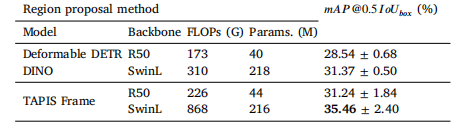

Table 4Performance of TAPIS in GraSP. We report the results of TAPIS on the test set of GraSP, and we compare its performance with a CNN-based baseline (SlowFast), the TAPIRmodel proposed in Valderrama et al. (2022) and a Video Swin Transformer-based implementation (TAPIS-VST). We present the number of parameters (Params.) and floating pointoperations (FLOPs) of each model without counting the region proposal network. The best results are shown in bold.

表4 TAPIS模型在GraSP数据集上的性能表现 本表报告了TAPIS模型在GraSP数据集测试集上的性能结果,并将其与以下模型进行对比:基于CNN的基准模型(SlowFast)、Valderrama等人(2022)提出的TAPIR模型,以及基于视频Swin Transformer(VST)的实现版本(TAPIS-VST)。 表中还列出了各模型的参数数量(Params.)与浮点运算次数(FLOPs),计算时未包含区域建议网络(region proposal network)的参数与运算量。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

Table 5Comparative results of TAPIS in instrument and action presence recognition in GraSP.We report the results of our model on frame-wise prediction of instrument presenceand atomic action presence, regardless of location or instance count. The best resultsare shown in bold.

表5 TAPIS模型在GraSP数据集“器械存在识别”与“动作存在识别”任务中的对比结果 本表报告了TAPIS模型在“帧级器械存在预测”与“帧级原子级动作存在预测”任务上的性能结果(注:该任务仅判断器械/动作是否存在,不考虑其空间位置或实例数量)。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

Table 6Comparative results of TAPIS in Instrument and Interactions Detection on the EndoVis2018 dataset. We test our TAPIS model in the benchmark proposed in Islam et al.(2020) and compare our performance with previously proposed methods. The bestresults are shown in bold

表6 TAPIS模型在EndoVis 2018数据集“器械与交互检测”任务中的对比结果 我们在Islam等人(2020)提出的该基准测试任务上对TAPIS模型进行了测试,并将其性能与此前提出的各类方法进行对比。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

Table 7Comparative results of TAPIS on the gesture recognition task of the RARP-45 dataset.We compare the performance of TAPIS with SOTA models for phase recognition, andits alternative baseline architectures on gesture recognition in the dataset proposed byvan Amsterdam et al. (2022). The best results are shown in bold

表7 TAPIS模型在RARP-45数据集“手势识别”任务中的对比结果 在van Amsterdam等人(2022)提出的该数据集上,我们将TAPIS模型在“手势识别”任务中的性能,与用于“阶段识别”的最先进(SOTA)模型、以及TAPIS的其他基准架构(alternative baseline architectures)进行了对比。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

Table 8Comparative results of TAPIS in phases and steps recognition on the MISAW dataset.We compare the performance of TAPIS with SOTA models for phase recognition, andits alternative baseline architectures on Phase and Step recognition in the benchmarkproposed by Huaulmé et al. (2021). The best results are shown in bold.

表8 TAPIS模型在MISAW数据集“阶段与步骤识别”任务中的对比结果 在Huaulmé等人(2021)提出的该基准测试任务上,我们将TAPIS模型在“阶段识别”与“步骤识别”任务中的性能,与用于“阶段识别”的最先进(SOTA)模型、以及TAPIS的其他基准架构(alternative baseline architectures)进行了对比。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

Table 9Comparative results of TAPIS in phase and step recognition on GraSP’s cross-validation set. We evaluate the TAPIS trained for phase and step recognition jointly (multi-task) andindependently, and compare it with alternative baseline and SOTA models for surgical phase recognition trained independently. The best results are shown in bold.

表9 TAPIS模型在GraSP数据集交叉验证集“阶段与步骤识别”任务中的对比结果 本研究对TAPIS模型进行了两种训练方式的评估:一是联合训练(多任务模式),即同时训练“阶段识别”与“步骤识别”任务;二是独立训练,即分别单独训练两个任务。 同时,我们将上述两种训练方式下的TAPIS性能,与“用于手术阶段识别的其他基准架构”及“单独训练的最先进(SOTA)模型”进行了对比。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

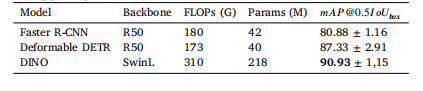

Table 10Comparative results in Instrument Detection in the cross-validation set. We testmultiple object detection architectures using the bounding boxes generated by GraSP’ssegmentation annotations. We also report the number of parameters (Params.) andfloating point operations (FLOPs) of each model. The best results are shown in bold

表10 交叉验证集中“器械检测”任务的对比结果 本研究使用由GraSP数据集分割标注生成的边界框,对多种目标检测架构进行了测试。表中同时报告了各模型的参数数量(Params.)与浮点运算次数(FLOPs)。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

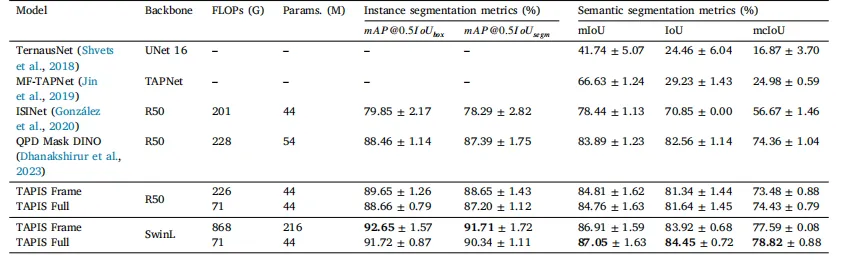

Table 11Comparative results of TAPIS in Instrument Segmentation in the cross-validation set. We showcase the instance and semantic segmentation performance of our instrumentsegmentation baseline (TAPIS Frame) and our complete model (TAPIS Full), and we compare it to our CNN baseline and previous state-of-the-art models for instrument segmentation.The parameters and floating point operations reported for the TAPIS Full models correspond to the video feature extractor and the region classification head while the valuesreported for TAPIS Frame correspond to Mask2Former. The best results are shown in bold.

表11 TAPIS模型在交叉验证集“器械分割”任务中的对比结果 本表展示了以下模型的实例分割与语义分割性能:TAPIS的器械分割基准模型(TAPIS Frame)、TAPIS完整模型(TAPIS Full),并将二者与“基于CNN的基准模型”及“此前用于器械分割的最先进(SOTA)模型”进行对比。 其中,TAPIS Full模型报告的参数数量与浮点运算次数,对应其视频特征提取器与区域分类头;TAPIS Frame模型报告的参数数量与浮点运算次数,对应其基础模型Mask2Former。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

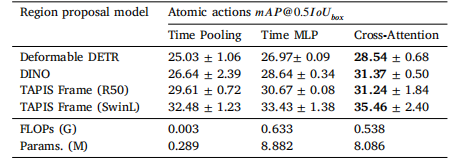

Table 12Comparative results of TAPIS in Atomic Action Detection. We present the results ofemploying region features from multiple detection and segmentation models. We alsoreport the number of parameters and floating point operations corresponding to theregion proposal networks. The best results are shown in bold.

表12 TAPIS模型在“原子级动作检测”任务中的对比结果 本表呈现了“采用来自多种检测与分割模型的区域特征”时的任务性能结果。同时,表中还报告了各模型所对应“区域建议网络(region proposal networks)”的参数数量与浮点运算次数。所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

Table 13Ablation results on the design of the region classification head in the cross-validationset. We compare the performance in atomic action detection using the Time Poolingdesign of Valderrama et al. (2022), the Time MLP from (Ayobi et al., 2023), and ournew Cross-Attention layer design. The best results are shown in bold

表13 交叉验证集中“区域分类头设计”的消融实验结果 本表对比了不同区域分类头设计在“原子级动作检测”任务中的性能,涉及三种设计方案: 1. Valderrama等人(2022)提出的时间池化(Time Pooling)设计; 2. Ayobi等人(2023)提出的时间多层感知机(Time MLP)设计; 3. 本研究提出的新型交叉注意力层(Cross-Attention layer)设计。 所有任务中的最佳性能结果以加粗字体显示。

Table 14Ablation results on atomic action fine-tunning. We evaluate the effect of Long-Termtasks pretraining and using pre-classified region embeddings (Class Regions) for atomicaction detection.

表14 原子级动作微调(fine-tuning)的消融实验结果 本表评估了两个关键因素对“原子级动作检测”任务性能的影响,分别为: 1. 长期任务预训练(Long-Term tasks pretraining):即先对阶段识别、步骤识别等长期任务进行训练,再将训练后的模型参数用于原子级动作检测任务的微调; 2. 使用预分类区域嵌入(pre-classified region embeddings,即Class Regions):即在原子级动作检测中,采用已预先完成类别分类的区域嵌入特征作为输入。